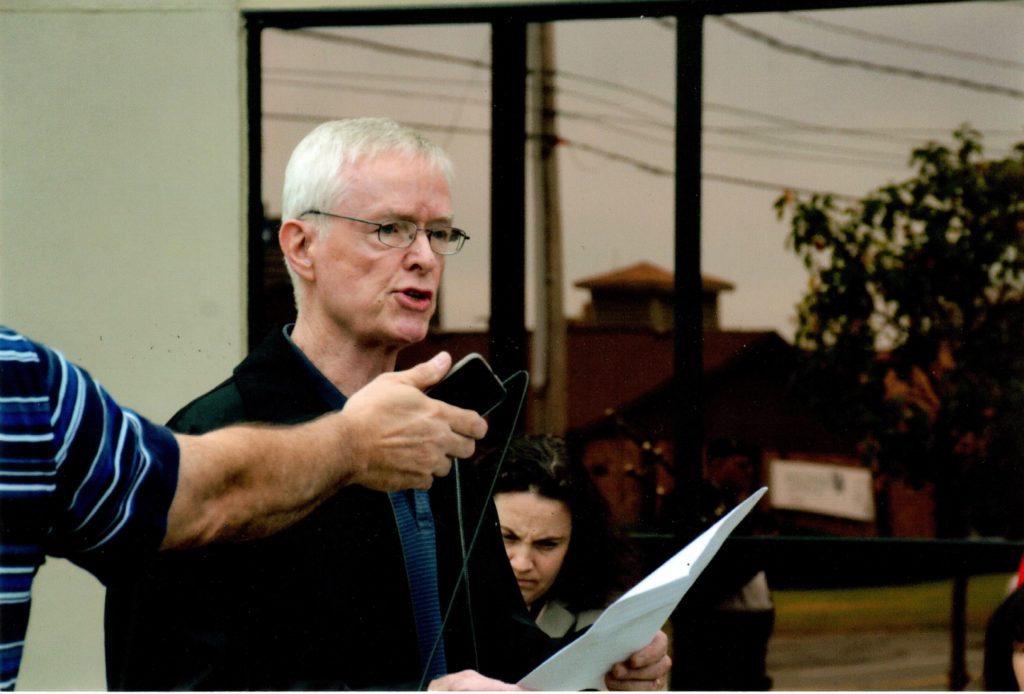

Addressing a group of vets attending a summer cook-out in 2016 at the VA Behavioral Health Center, Syracuse, NY.

Following are links to a few of my published stories:

Why I write

I wrote this story because I wanted to know why. I became a moneychanger with the empty suits and charlatans, the social and economic elite, the pinky rings and silver spoons; we had nothing in common. They never served. Their sons and daughters never served. They went to the Country Club, flew to Monaco and St. Moritz, managed their investments, traveled to homes in the mountains and on the seacoast. They’d court customers in good times and kick them out when times were tough. I held them in contempt for turning their backs and was fired for insubordination. If not for my VA pension, I’d be travelling from park bench to cardboard box. I want to know why; why didn’t I play the game? Continue reading:

Minefield

Claymore mines and concertina wire lined the perimeter of our camp. The territory beyond that was littered with old mines, buried years before by the French. We cleared what we could when we built our camp, but there were still leftovers. Every so often, someone would wander off the road and trip one of them. We’d get the casualties at the dispensary. Most were DOA. Continue reading:

https://surface.syr.edu/intertext/vol20/iss1/19

VA Shrink

The innocuous label in the lobby said “Behavioral Health.” Standing in an elevator full of people, a month before the reunion, I didn’t want to be seen pushing that button, but there I was at 60 years old, seeing a shrink for the first time in my life.

I had heard vets talk about the eighth floor of the VA Medical Center. It was for the nut cases who made civilians nervous. I thought they might have been joking until I stepped off the elevator. There weren’t any examining rooms or weight scales in the hallway, and no hospital smell. It looked like a floor in an office building, far removed from the typical clinics and the daily bustle of the hospital, except for the VA cop stationed near the front desk. After checking in, I sat in a waiting room with vets who didn’t feel dangerous, but rather pensive and subdued. One of them kept rubbing his hands together like he was cold. Another, with long greasy hair and dressed in old fatigues, just stared at the floor. There was no eye contact and no conversation. Continue reading:

Perez

For years, I believed that I had failed on the Bunard mission, the firefight during which Perez and I got wounded. If I hadn’t been following him, I wouldn’t have been shot. He could have been grandstanding for a medal, something I’d expect from a young officer, not a seasoned one. Rushing into an enemy position was not SOP on our team, but that’s what he did. He could have learned it in one of the basic infantry tactic classes in Officer Candidate School—classic operations where you can see the enemy—WWI, WWII, Korea. It doesn’t work in the jungle. You can’t see the enemy. You can’t see your own men. Continue Reading:

Little Pine Creek Club

Published in Shooter Literary Magazine, Issue #1, Winter 2015.

I never considered hunting until after the service. As a kid, I knocked over tin cans with my .22 but never went after animals. Bob Turnbull, a friend from Sandy Pond and a champion New York State archer, got me interested in bowhunting. About my age, he was thick set and funny as hell once he had a few Tanqueray and tonics in his tank. At his invitation, I joined a weekly archery league my first semester back at SU, and practiced every day before bow season. It was the only respite I had during that tumultuous spring on campus. We hunted down in the Southern Tier on state land. I’d been down there the previous summer hiking in the pristine forest, having taken a weekend break from rehab at Saint Albans Hospital. It reminded me of Uhwarrie National Forest, except on a smaller scale. I lost myself in the majesty of the landscape. Bordered by apple orchards and cornfields, it was good habitat for Whitetail Deer. Hunting there appealed to me. I was back playing war games at Bragg—it was just me and the enemy. I felt powerful and in control.

I bought a Browning recurve hunting bow, compact but powerful enough to drive a razor-tipped aluminum shaft clear through a deer at 30 yards. I shot bare-bow, with no sight, instinctive shooting the way the American Indians had hunted. It leveled the playing field. I’d paint up my face in camo, put on my fatigues and stalk deer. The first time out on a wet and miserable October day, I nailed a buck. Turnbull couldn’t believe it; he had bow hunted for five years but never bagged one. I sensed where the deer were and I was patient. I’d wait for them to make a mistake, then they were mine.

Initially, it was the adrenaline rush of pursuit and kill, but communion followed—total and complete domination of my prey. I found curious satisfaction in eviscerating the animals. Once I slit the belly open, intestines spilled onto the forest floor like a steaming plate of pasta. The metallic smell of blood left that familiar taste in my mouth. I’d palpate the piping hot organs in the abdominal cavity for the esophagus, trachea, heart, and bladder, which needed to be carefully cut and removed. Then I’d drag the animal to my truck. After hanging the carcass from a tree limb in the back yard for several days to drain any remaining blood and allow the meat to age, I’d butcher it.

I continued to bowhunt for several years but was having trouble with repeated shoulder injuries suffered in karate, racquetball, and downhill skiing. I didn’t have the strength to pull and hold an arrow at full draw for any length of time, and switched to a sight-less compound bow that offered a 30 percent let-off in draw weight, but it was only a question of time before I couldn’t handle that, either. Finally, after tearing both rotator cuffs, I was finished bowhunting.

***

A friend named Tremont belonged to an Adirondack hunting camp and he invited me up once a year for a weekend gun hunt. Little Pine Creek Club was situated on 2,000 acres of prime woodland loaded with maple, walnut and cherry. The camp building was recent, built in the early 1970s, with a massive stone fireplace, generator, full kitchen, hot and cold running water, full bathroom with shower, bar, and a bunk house off from the kitchen. The terrain was challenging, with rolling hills and deep gullies that flooded during heavy rain. Logging trails crisscrossed the parcel, allowing members to use a truck to ride to any of a dozen hunting locations, which were all mapped. You’d have to be an imbecile to get lost there, but every season a guest would do just that. Two streams ran through the property and it was bordered on one side by a massive state park, and on the other three by private hunting camps. The club was two miles off the paved highway on a gated graveled road that ran through the forest from Brantingham Lake to Stillwater. Ten camps were on that road, including Little Pine Creek. The club had 17 members, not all active, but weekends we’d have 15 to 20 guys prowling the grounds. It was basically a social club, and members were selective about who they’d invite up for a weekend. The members were experienced hunters and it was a family affair with several grandfather, father, and son teams. It was a great place to introduce a boy into the hunting ritual.

It took me almost 20 years, until 1997, before I was offered a membership. I felt honored and especially excited about the prospect of bringing my sons up to mingle with the members and learn how to hunt without having to worry about being shot by some careless jerk. I felt a kinship of sorts with the members and expected friendships to grow. Perhaps I was in search of the same comradeship I had in Special Forces, but it never materialized. I never felt the same closeness or level of trust. They were decent men, and we had lots of laughs, but I didn’t like how we hunted. It wasn’t challenging. In fact, there was no challenge to it at all. The hunting was done in drives: half of us would be stationed on a watch, while the other half would drive deer to the watchers. It wasn’t sportsman like, but it was a way to get out in the woods and get some exercise. Some of us hunted alone from tree stands, and a few guys bowhunted, but the majority of the members weren’t as adventurous. There were members in their 70s and 80s who still hunted, and the watch and drive method was the only way that they would see any hunting action. The younger guys took care of the old guys in the field, made sure they were given a good watch in return for the training they had received as youngsters. From that standpoint, I liked the club, because I could see myself growing old with my sons.

Keith liked the outdoors but never developed an interest in hunting. I had taken him bowhunting once when he was a teenager on a cold and rainy day. We stood for hours waiting for deer to move. He was wet and miserable, and quickly lost interest. Rich tried it a few times, but he, too, had other interests and never got into it. It was Ben who loved to hunt. His first time out, he nailed a six-point buck. He was on a watch across a ravine from me, and I heard five quick shots from his .30 caliber lever action Winchester, the same gun Chuck Connors, “The Rifleman” used, which he’d shoot from the hip. Ten minutes later, I helped Ben track down his buck. I often look at the photo of him and me standing next to his buck, hanging on the buck pole at camp. That evening at the camp bar, we congratulated Ben for his good fortune that day, and he got the nickname The Rifleman from then on. The members loved Ben and it made me proud, but I never felt one with the members. Maybe I was just asking too much of their friendship.

A year after the PTSD diagnosis, I was hunting with some friends and we were driving private land south of Fabius. I was on watch, standing behind several windfalls, and saw a large doe come into range. She was in her prime, maybe two or three years old, probably a mother twice over. As she browsed at the base of a cherry tree for star moss, I put the “V” of my open rear sight on her ribcage just behind the shoulders, lined it up with the bead at the end of the barrel, hesitated for a second, and gently squeezed the trigger. She dropped in a heap. I thought it was a good shot, only about 30 yards. I stood still for a few moments so as not to spook her, listening for any movement, but all I heard was the faint cry of a baby. I thought I was dreaming, that I wasn’t really hearing this, that my mind was playing a trick on me, but the doe wailed on, and what came to mind was the thought of my own children, hungry or wet and in distress, a Cambodian child crying in my dispensary, a Vietnamese child crying for the attention of a dead parent. At that moment, I didn’t know what to do—finish her off, or try to save her. The faces of wounded strikers flashed through my mind, the ones I couldn’t help because it was against orders. I’d watch them bleed to death. I played God. I was their judge and jury. They were guilty of helping us drive the commies out of their own homes. I was guilty of murder, of turning my back on another human being. I had to do something.

I moved in to get a closer look at her wound and she panicked. Lifting her head off the ground, I saw fright in her eyes, the enemy staring her down with a 12-gauge shotgun. She struggled to get up but fell back on her haunches. The slug had entered her abdominal cavity just beneath the diaphragm, which meant that it could be hours before she bled out. I had to finish the job. As I moved closer, she squirmed and tried to get up on her haunches again. I had to put her out of her misery. I put a slug into her chest, and she went down, but she wasn’t dead. Wailing, I pulled out my knife to slit her throat, but thought the better of it. I was shaking now, despondent over what I had done, but I knew the only humane thing to do was to kill her. I was about 10 feet from her and as she craned her head toward me again, I fired slug after slug into her chest but she wouldn’t die. It was like a slow-motion scene during a firefight. I ran out of ammo, and she was still breathing. I set my shotgun against the cherry tree, and sat with my back against the tree and watched her chest rise and fall for a few minutes until she took her last breath. The heat from her body escaped into the atmosphere, giving rise to wisps of vapor in the cold morning air. I put my hand on her head. Her eyes were open, an eternal stare for me to remember. Her tongue was flaccid and emerged from between her teeth, much like the onset of death in humans. I took a deep breath and thanked God that it was over.

“I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”

I couldn’t move. I was catatonic. It took me another half an hour to come to my senses before I gutted and dragged her to my truck. I never took any game without the express intent of consuming the meat, and this doe was no exception, except that she was the last deer I would ever kill.

After that, I looked differently at hunting. I realized that I never enjoyed the killing part. I’d shake in nervous anticipation, adrenaline coursing through my body, hesitate before releasing the arrow or squeezing the trigger. I remembered what Andy Olsen, the sales manager in my father’s office, had said about my dad not having the killer instinct. I didn’t have the killer instinct either, the thing I thought would make me feel like a man. I began to think about Little Pine Creek and the way that we drove deer, unfairly trapping them in the panic of flight. It wasn’t a fair fight. Using a gun wasn’t fair. I had stopped hunting fairly when I put down my bow. But there was more to it. I was conflicted.

The week after the incident with the doe, I had one of my VA group meetings at the behavioral health center and I told the guys how I felt about shooting that doe, and that I really didn’t want to hunt anymore. I told them about the camp, that I never really felt like I belonged, but I didn’t want to let the members down by quitting.

“Who are these guys, and what do you owe them?”

I scanned their faces and tried to think of an answer. I shrugged my shoulders.

“I don’t know.”

“Are they your buddies?”

I had to think about that too. They were friends, but after hunting season, we went our separate ways. The camaraderie was short lived.

“I suppose not.”

“Why else would you want to stay?”

Ben was the only reason, and he was now married with children and had demands on his time. He seldom went up to camp with me.

“There is no other reason.”

“Then follow your heart, man.”

That I did. I resigned. The members didn’t understand why. There were only three vets in the club, and I told one of them I had PTSD, and that I didn’t want to hunt anymore. He was a WWII vet and I don’t think he understood.

While the adrenaline rush was part of the lure of hunting, I learned in therapy that hunting was a reaction to the helplessness I felt in the jungles of Vietnam, being hunted by a worthy enemy, out of control, afraid for my life. Back home, I went out in the woods looking for the enemy. I was the one in control.